Bobby Sands: dal ghetto nazionalista alla battaglia nei Blocchi H

BOBBY SANDS | From a nationalist ghetto to the battlefield of H-Block

The birth of a republican

‘THE BIRTH of a republican: from a nationalist ghetto to the battlefield of H-Block’, by hunger-striker Bobby Sands, was first published anonymously in Republican News on December 16th 1978. It was reprinted in An Phoblacht/Republican News on April 4th 1981, after Bobby had been on hunger strike for one month.

The smuggled-out article, introduced as “A blanket man recalls how the spirit of a republican defiance grew within him”, is a semi-autobiographical account. For example, although blanket men had been denied compassionate parole for the funeral of a parent, as described in the article, Bobby Sands’s mother was very much alive and, in fact, she addressed the Belfast rally held on the first day of his hunger strike, calling for support for her son to save his life.

FROM MY earliest days I recall my mother speaking of the troubled times that occurred during her childhood.

Often she spoke of internments on prison ships, of gun attacks and death, and early morning raids when one lay listening with pounding heart to heavy clattering of boots on the cobble-stone streets, and as a new day broke, peeked carefully out the window to see a neighbour being taken away by the Specials.

Although I never really understood what internment was, or who the Specials were, I grew to regard them as symbols of evil. Nor could I understand when my mother spoke of Connolly and the 1916 Rising and of how he and his comrades fought and were subsequently executed – a fate suffered by so many Irish rebels in my mother’s stories.

When the television arrived, my mother’s stories were replaced by what it had to offer. I became more confused as ‘the baddies’ in my my mother’s tales were always my heroes on the TV. The British Army always fought for ‘the right side’ and the police were always ‘the good guys’. Both were heroised and imitated in childhood play.

SCHOOL

At school I learnt history but it was always English history and English historical triumphs in Ireland and elsewhere.

I often wondered why I was never taught the history of my own country when my sister, a year younger than myself, began to learn the Gaelic language at her school I envied her. Occasionally, nearing the end of my schooldays, I received a few scant lessons in Irish history. For this, from the republican-minded teacher who taught me, I was indeed grateful.

I recall my mother also speaking of ‘the good old days’. But of her marvellous stories I could never remember any good times and I often thought to myself ‘Thank god I was not a boy in those times’ because then– having left school – life to me seemed enormous and wonderful.

Starting work, although frightening at first, became alright, especially with the reward at the end of the week. Dances and clothes, and girls and a few shillings to spend opened up a whole new world to me. I suppose at that time I would have worked all week as money seemed to matter more than anything else.

CHANGE

Then came 1968 and my life began to change. Gradually the news began to change. Regularly I began to notice the Specials (whom I now know to be the ‘B’ Specials) attacking and baton-charging the crowds of people who all of a sudden began marching on the streets.

From the talk in the house and my mother shaking her fists at the TV set, I knew that they were our people on the receiving end.

My sympathy and feelings really became aroused after watching the scenes at Burntollet. That imprinted itself in my mind like a scar, and for the first time I took a real interest in what was going on.

I became angry.

It was now 1969, and events moved faster as August hit our area like a hurricane. The whole world exploded and my whole little world crumbled around me.

The TV did not have to tell the story now for it was on my own doorstep. Belfast was in flames but it was our districts, our humble homes, which were burnt. The Specials came at the head of the RUC and Orange hordes, right into the heart of our streets, burning, looting, and murdering.

There was no one to save us except ‘the boys’, as my father called the men who were defending our district with a handful of guns. As the unfamiliar sound of gunfire was still echoing, there soon appeared alien figures, voices, and faces, in the form of British armed soldiers on our streets. But no longer did I think of them as my childhood ‘good guys’, for their presence alone caused food for thought.

Before I could work out the solution, it was answered for me in the form of early-morning raids and I remember my mother’s stories of previous troubled times. For now my heart pounded at the heavy clatter of the soldiers’ boots in the early-morning stillness and I carefully peeked from behind the drawn curtains to watch the neighbours’ doors being kicked in and the fathers and sons being dragged out by the hair and being flung into the back of sinister-looking armoured cars.

This was followed by blatant murder: the shooting dead of people in our streets in cold blood.

The curfew came and went, taking more of our people’s lives.

IRA

Every time I turned around a corner I was met with the now all-too-familiar sight of homes being wrecked and people being lifted. The city was in uproar. Bombings began to become more regular, as did gun battles as ‘the boys’, the IRA, hit back at the Brits.

Every time I turned around a corner I was met with the now all-too-familiar sight of homes being wrecked and people being lifted. The city was in uproar. Bombings began to become more regular, as did gun battles as ‘the boys’, the IRA, hit back at the Brits.

The TV now showed endless gun battles and bombings. The people had risen and were fighting back and my mother, in her newly-found spirit of resistance, hurled encouragement at the TV, shouting “Give it to them, boys!”

Easter 1971 came and the name on everyone’s lips was ‘the Provos – the People’s Army’, the backbone of nationalist resistance.

I was now past my 18th year and I was fed up with rioting. No matter how much I tried or how many stones I threw, I could never beat them – the Brits always came back . . .

I had seen too many homes wrecked, fathers and sons arrested, neighbours hurt, friends murdered, and too much gas, shootings and blood – most of it my own people’s.

At eighteen-and-a-half I joined the Provos. My mother wept with pride and fear as I went out to meet and confront the imperial might of an empire with an M1 carbine and enough hate to topple the world.

To my surprise, my schoolday friends and neighbours became my comrades in war. I soon became much more aware about the whole national liberation struggle – as I came to regard what I used to term ‘the Troubles’.

OPERATIONS

Things were not easy for a Volunteer in the Irish Republican Army. Already I was being harassed and twice I was lifted, questioned, and brutalised, but I survived both of these trials.

Then came another hurricane: internment. Many of my comrades disappeared – interned.

Many of my innocent neighbours met the same fate. Others weren’t so lucky – they were just murdered.

My life now centred around sleepless nights and standbys, dodging the Brits and calming nerves to go out on operations.

But the people stood by us.

The people not only opened the doors of their homes to us to lend a hand but they opened their hearts to us, and I soon learnt that without the people we could not survive and I knew that I owed them everything.

1972 came and I spent what was to be my last Christmas at home for quite a while. The Brits never let up. No mercy was shown, as was testified by the atrocity of Bloody Sunday in Derry.

But we continued to fight back, as did my jailed comrades, who embarked upon a long hunger strike to gain recognition as political prisoners.

Political status was won just before the first but short-lived, truce of 1972. During this truce the IRA made ready and braced itself for the forthcoming massive Operation Motorman, which came and went, taking with it the barricades.

The liberation struggle forged ahead but then came personal disaste– I was captured.

It was the autumn of ’72. I was charged and for the first time I faced jail. I was nineteen-and-a-half, but I had no alternative than to face up to all the hardship that was before me.

Given the stark corruptness of the judicial system, I refused to recognise the court. I ended up sentenced in a barbed wire cage, where I spent three-and-a-half years as a prisoner-of-war with ‘special category status’.

I did not waste my time. I did not allow the rigours of prison life to change my revolutionary determination an inch. I educated and trained myself both in political and military matters, as did my comrades.

In 1976, when I was released, I was not broken. In fact I was more determined in the fight for liberation. I reported back to my local IRA unit and threw myself straight back in to the struggle.

Quite a lot of things had changed. Belfast had changed. Some parts of the ghettos had completely disappeared and others were in the process of being removed. The war was still forging ahead although tactics and strategy had changed.

At first I found it a little bit hard to adjust but I settled into the run of things and, at the grand old age of 23, I got married.

Life wasn’t bad but there were still a lot of things that had not changed, such as the presence of armed British troops on our streets and the oppression of our people.

The liberation struggle was now seven years old and had braved a second (and mistakenly-prolonged) ceasefire.

The British Government was now seeking to ‘Ulsterise’ the war, which included the attempted criminalisation of the IRA and attempted normalisation of the war situation.

The liberation struggle had to be kept going. Thus, six months after my release, disaster fell a second time as I bombed my way back into jail!

CAPTURE

With my wife being four months pregnant, the shock of capture, the seven days of hell in Castlereagh, a quick court appearance and remand, and the return to a cold damp cell, nearly destroyed me. It took every ounce of the revolutionary spirit left in me to stand up to it.

Jail, although not new to me, was really bad, worse than the first time. Things had changed enormously since the withdrawal of political status. Both republicans and loyalist prisoners were mixed in the same wing.

The greater part of each day was spent locked up in a cell. The Screws, many of whom I knew to be cowering cowards, now went in gangs into the cells of republican prisoners to dish out unmerciful beatings. This was to be the pattern all the way along the road to criminalisation: torture and more torture to break our spirit of resistance. I was meant to change from being a revolutionary freedom fighter to a criminal at the stroke of a political pen, reinforced by inhumanities of the most brutal nature.

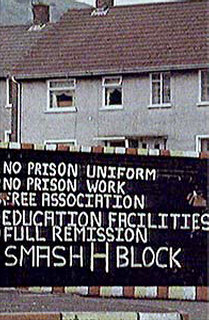

Already Kieran Nugent and several more republican POWs had begun the blanket protest for the restoration of political status. They refused to wear prison garb or to do prison work.

After many weekly remand court appearances the time finally arrived, 11 months after my arrest and I was in a Diplock [no-jury] court. In two hours I was swiftly found guilty and my comrades and I were sentenced to 15 years. Once again I had refused to recognise the farcical judicial system. As they led us from the courthouse, my mother, defiant as ever, stood up in the gallery and shook the air with a cry of “They’ll never break you, boys!” And my wife from somewhere behind her, with tear-filled eyes, braved a smile of encouragement towards me.

At least, I thought, she has our child. Now that I was in jail, our daughter would provide her with company and maybe help to ease the loneliness which she knew only too well.

The next day I became a blanket man and there I was, sitting on the cold floor, naked, with only a blanket around me, in an empty cell.

H-BLOCKS

The days were long and lonely. The sudden and total deprivation of such basic human necessities as exercise and fresh air, association with other people, my own clothes, and things like newspapers, radio, cigarettes, books and a host of other things made life very hard.

The days were long and lonely. The sudden and total deprivation of such basic human necessities as exercise and fresh air, association with other people, my own clothes, and things like newspapers, radio, cigarettes, books and a host of other things made life very hard.

At first, as always, I adapted. But, as time wore on, I came face to face with an old ‘friend’, depression, which on many occasion consumed me and swallowed me into its darkest depths.

From home, only the occasional letter got past the prison censor.

Gradually my appearance and physical health began to change drastically. My eyes, glassy, piercing, sunken, and surrounded by pale, yellowish skin, were frightening.

I had grown a beard and, like my comrades, I resembled a living corpse. The blinding migraine headaches, which started off slowly, became a daily occurrence, and owing to no exercise I became seized with muscular pains.

In the H-Blocks, beatings, long periods in the punishment cells, starvation diets and torture were commonplace.

March 20th 1978, and we completed the full circle of deprivation and suffering. As an attempt to highlight our intolerable plight, we embarked upon a dirt strike, refusing to wash, shower, clean out our cells or empty the filthy chamber pots in our cells.

The H-Blocks became battlefields in which the republican spirit of resistance met head-on all the inhumanities that Britain could perpetrate.

Inevitably, the lid of silence on the H-Blocks blew sky-high, revealing the atrocities inside.

The battlefield became worse: our cells turning into disease-infested tombs with piles of decaying rubbish and maggots, fleas and flies becoming rampant. The continual nauseating stench of urine and the stink of our bodies and cells made our surroundings resemble a pigsty.

The Screws, keeping up the incessant torture, hosed us down, sprayed us with strong disinfectant, ransacked our cells, forcibly bathed us, and tortured us to the brink of insanity. Blood and tears fell upon the battlefield – all of it ours. But we refused to yield.

PROUD

The republican spirit prevailed and as I sit here in the same conditions and the continuing torture in H-Block 5, I am proud, although physically wrecked, mentally exhausted, and scarred deep with hatred and anger.

I am proud because my comrades and I have met, fought and repelled a monster and we will continue to do so. We will never allow ourselves to be criminalised, nor our people either.

Grief-stricken and oppressed, the men and women of no property have risen. A risen people, marching in thousands on the streets in defiance and rage at the imperial oppressor, the mass murderer, and torturer. The spirit of Irish freedom in every single one of them – and I am really proud.

Last week, I had a visit from my wife, standing by me to the end as ever. She barely recognised me in my present condition and in tears she told me of the death of my dear mother – God help her, how she suffered.

I sat in tears as my wife told me how my mother marched in her blanket, along with thousands, for her son and his comrades, and for Ireland’s freedom.

When the Screws came to tell me that I was not getting out on compassionate parole for my mother’s funeral, I sat on the floor in the corner of my cell and I thought of her in Heaven, shaking her fist in her typical defiance and rage at the merciless oppressors of her country. I thought, too, of the young ones growing up now in a war-torn situation and, like my own daughter, without a father, without peace, without a future, and under British oppression. Growing up to end up in Crumlin Road Jail, Castlereagh, barbed-wire cages, Armagh Prison and Hell-Blocks.

Having reflected on my own past, I know this will occur unless our country is rid of the perennial oppressor, Britain. And I am ready to go out and destroy those who have made my people suffer so much and so long.

I was only a working-class boy from a nationalist ghetto but it is repression that creates the revolutionary spirit of freedom.

I shall not settle until I achieve the liberation of my country, until Ireland becomes a sovereign, independent socialist republic.

We, the risen people, shall turn tragedy into triumph. We shall bear forth a nation!

One Comment