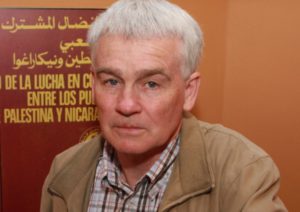

Tommy McKearney, condannato nel 1976 per avere ucciso Stanley Adams, membro UDR part-time e postino, ha detto che anche numerosi repubblicani hanno poco interesse a rimuovere il confine.

Nel libro presentato la scorsa notte nella zona ovest di Belfast, McKearney sostiene che l’unico modo per i repubblicani per rimuovere la frontiera è di cooperare insieme alla classe operaia protestante, nel tentativo di creare una Irlanda socialista.

Nel suo libro, The Provisional IRA, From Insurrection to Parliament (Provisional IRA; Dall’insurrezione al Parlamento), dice: “l’unità irlandese rimane un’aspirazione per molti – ma solo un’aspirazione.

“Un pensiero piacevole, ma non qualcosa per cui la maggior parte della gente si prepara ad investire tempo o energia”.

Sostiene che, sebbene lo Sinn Fein continui ad affermare che l’Accordo del 1998 “potrebbe affrettare il giorno dell’unità irlandese”, ad oltre un decennio da quel momento non c’è stata alcuna significativa erosione del supporto allo Sinn Fein, nonostante l’assenza di movimento verso un’Irlanda unita.

Questo, suggerisce McKearney, dimostra che la maggior parte dei sostenitori dello Sinn Fein comprende – ed accetta – la realtà che l’accordo in realtà ha cementato la partizione.

McKearney ha parole al fulmicotone anche per il tentativo odierno da parte dei repubblicani di usare le bombe per ottenere l’Irlanda unita, descrivendoli come “irrilevanti anacronismi”.

Accusa i gruppi armati dissidenti – come Real IRA e Continuity IRA – come individui non focalizzati con un “feticcio per le armi”, affermando che hanno creato “uno dei grandi paradossi dell’attuale Irlanda del Nord”, distogliendo l’attenzione dai fallimenti dello Sinn Fein.

E, dice, che “non importa quanto irritati” possano essere quei repubblicani che continuano a bombardare e sparare, la loro influenza è “minimo”.

L’ardente socialista, che adesso organizza il sindacato Independent Workers’ Union, afferma che lo Sinn Fein è diventato sempre più di destra mentre stava sempre di più nel governo a Stormont dove, sostiene, “contrariamente a parlare di condivisione del potere, l’amministrazione [di Stormont] amministrazione è quasi impotente” perché non ha il controllo dell’economia.

L’accordo tra Ian Paisley e Martin McGuinness, prosegue McKearney, termina “la questione nazionale irlandese”.

“Per alcuni è stato difficile da accettare, era chiaro che nessuno nella società irlandese all’epoca era pronto a contestare in alcun modo l’assetto costituzionale dell’isola.

“Il popolo irlandese aveva votato in massa per l’Accordo del Venerdì Santo nel 1998 e da allora sono rimasti fedeli ai suoi promotori ad ogni tornata elettorale.

“Rimane, naturalmente, un’aspirazione largamente condivisa, ma non intensamente voluta, che le Sei Contee un giorno potranno finire nella giurisdizione di Dublino.

“Per la grande maggioranza, però, è un’aspirazione lontana che non riesce a causare altro che nostalgia occasionale”.

Prosegue la sua analisi osservando come i repubblicani ora abbiano bisogno di impegnarsi attivamente con la classe operaia protestante per costruire il supporto per un’Irlanda socialista perché “una sola piattaforma repubblicana tesa a rompere l’Unione e a far terminare la partizione non è in grado di mobilitare un sostegno sufficiente per il tipo di cambiamento fondamentale richiesto”.

Per McKearney anche Ian Paisley sostiene che l’Accordo di Belfast era un “tradimento” che ha permesso allo Sinn Fein di illudere i più intransigenti membri dell’IRA, facendo credere loro di essere sul percorso di una Irlanda unita.

“La leadership repubblicana è stata molto aiutata dalla reazione isterica del DUP che, per proprie ragioni tattiche, insisteva a definire l’accordo un tradimento dell’Unione.

“Al contrario, è stato il leader dell’Ulster Unionist Party, David Trimble, a descrivere la situazione con maggiore accuratezza.

“Ricordava a tutti che accettare lo status quo costituzionale – modificabile solo da un voto di maggioranza nelle Sei Contee – faceva sì che l’accordo del Venerdì Santo, in realtà, assicurasse il futuro dell’Irlanda del Nord all’interno del Regno Unito”.

Tuttavia, nonostante il fallimento dell’RA di garantire un’Irlanda unita, l’ex militante armato repubblicano insiste sul fatto che in parte ha avuto successo, mettendo fine al dominio unionista dell’Irlanda del Nord.

“L’insurrezione armata è riuscita a rendere trasparente la natura e lo scopo della vita repressiva e oppressiva politica dello stato orangista… era una guerra di trasformazione”.

Nell’indice del libro di Tommy McKearney non viene fatto di alcun riferimento alla sua vittima.

Ma il libro Lost Lives (Vite perdute) racconta che in un programma della BBC andato in onda nel 1994, McKearney difese la sua azione di uccidere il giovane postino.

Disse all’epoca: “Un membro UDR fuori servizio resta un membro dell’esercito britannico. Ora, è ingenuo all’inverosimile credere che un uomo che consegna il latte, porta la posta o guida il bus della scuola mette da parte il suo ruolo [militare], mentre consegna o guida…”

Tratto da News Letter

Union is secure, says ex-IRA man

Tommy McKearney (inset right), who was convicted of murdering part-time UDR man Stanley Adams in 1976 while he was working as a postman, said that even many republicans now have little interest in removing the border.

In a book launched last night in west Belfast, he argues that the only way for republicans to now remove the border is for them to work with working class Protestants in an attempt to create a socialist Ireland.

In his book, The Provisional IRA, From Insurrection to Parliament, he says: “Irish unity remains an aspiration for many – but only an aspiration.

“A pleasant thought, but not something in which most people are prepared to invest time or energy.”

He argues that although Sinn Fein still pays lip-service to the claim that the 1998 Agreement “would hasten the day of Irish unity”, over a decade since that point there has been no significant erosion of support for Sinn Fein, despite no movement towards a united Ireland.

That, he suggests, shows that most Sinn Fein supporters understand — and accept — the reality that the agreement actually cemented partition.

Mr McKearney is equally withering about the attempts of today’s armed republicans to bomb their way to a united Ireland, describing them as “anachronistic irrelevance”.

He dismisses armed dissident groups — such as the Real IRA and Continuity IRA — as unfocussed individuals with an “arms fetish” and claims that they have created “one of the great paradoxes in contemporary Northern Ireland”, by diverting attention from the failures of Sinn Fein.

And, he says, that “no matter how peeved” those republicans who continue to bomb and shoot may be, their influence is “minimal”.

The ardent socialist, who now organises the Independent Workers’ Union, says that Sinn Fein has become increasingly right wing as it has gone further and further into government at Stormont, where, he argues, “contrary to talk of power-sharing, the [Stormont] administration is almost powerless” because it lacks control over the economy.

He says that the deal between Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness ended ‘the Irish national question’ for most.

“Difficult though it was for some to accept, it was clear that no significant section of Irish society was prepared at that time to contest in any determined fashion the constitutional arrangements on the island.

“Irish people had voted in huge numbers for the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 and have stayed loyal to its promoters at each election since.

“There remains, of course, a widely-shared but not intensely sought-after aspiration that the Six Counties might one day come under Dublin’s jurisdiction.

“For the vast majority, though, it is a distant aspiration that fails to motivate anything other than occasional nostalgia.”

He argues that republicans now need to actively engaged with working class Protestants to build support for a socialist Ireland as “a one-plank republican platform confined to breaking the Union and ending partition is not capable of mobilising sufficient support to bring about the type of fundamental change required”.

He also says that Ian Paisley’s claims that the 1998 Belfast Agreement were a “sell-out” helped Sinn Fein delude more hardline IRA members into believing that they were on the path to a united Ireland.

“The republican leadership was greatly helped by the hysterical reaction of the DUP who, for its own tactical reasons, was insisting that the agreement was a betrayal of the Union.

“In contrast, it was the Ulster Unionist Party leader David Trimble who described the situation most accurately.

“He reminded everyone that accepting the constitutional status quo could only be changed by a majority vote in the six counties meant that the Good Friday Agreement in reality had secured the future of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom.”

However, despite the failure of the IRA to secure a united Ireland, the former gunman insists that they partially succeeded by ending unionist dominance of Northern Ireland.

“The armed insurgency was successful in so far as it made transparent the nature and purpose of the Orange state’s repressive and oppressive political life…this was a transformative war”.

The index of Mr McKearney’s book records no references to his victim.

But the book Lost Lives recounts that in a 1994 BBC programme McKearney defended his actions in murdering the young postman.

He said then: “An off-duty UDR man is a member of the British Army. Now it is very naive and stretching credulity to breaking point to suggest that a man delivering the milk, delivering the mail or driving the school bus sets aside his [military] role while delivering or driving…”