Fare thee well, Lansdowne Road!

Damiano Benzoni

130 years through enrolments, mutinies and marriage proposals: the temple of Irish rugby closes down

On the 31st december Dublin said its farewell to one of the city’s monuments: Lansdowne Road, the venue which hosted the Irish rugby and football national teams. More than 130 years passed by this stadium, wholly built in wood, as if to give it the resemblance of a casket, full of tales and soaked with history. The casket will be demolished: in 2009 a modern all-seater will take its place, despite the anger of sport-tradition lovers and the criticism of the building committees, saying that the new stadium will disfigure the Ballsbridge neighbourhood, in the Dublin 4 area. The redevelopment got pressing when, in November 2005, a fire spreaded on the North Terrace the night before an important rugby match between Ireland and the All Blacks. The Irish rugby team saluted Lansdowne Road with a series of famous victories against the likes of South Africa, Australia and the Pacific Islanders in the November test-matches.

On the 31st december Dublin said its farewell to one of the city’s monuments: Lansdowne Road, the venue which hosted the Irish rugby and football national teams. More than 130 years passed by this stadium, wholly built in wood, as if to give it the resemblance of a casket, full of tales and soaked with history. The casket will be demolished: in 2009 a modern all-seater will take its place, despite the anger of sport-tradition lovers and the criticism of the building committees, saying that the new stadium will disfigure the Ballsbridge neighbourhood, in the Dublin 4 area. The redevelopment got pressing when, in November 2005, a fire spreaded on the North Terrace the night before an important rugby match between Ireland and the All Blacks. The Irish rugby team saluted Lansdowne Road with a series of famous victories against the likes of South Africa, Australia and the Pacific Islanders in the November test-matches.

Lansdowne Road hosted many events, apart from the football and rugby matches of the national representatives and from the FAI Cup finals. Two Heineken Cup finals took place at the stadium, in 1999 and 2003, and the ground has been used for concerts by artists including U2, Oasis, the Eagles and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. UEFA chairman Lars-Christer Olsson suggested that the new Lansdowne Road may host the UEFA Cup final in 2010 and the European Under 21 Championship final in 2011.

Bóthar Lansdún (the gaelic name of the field) can boast being the oldest rugby stadium in the World: it opened in 1872, when Henry William Dunlop, owner of 28 hectares of land between the river Dodder and the Lansdowne train station, founded Lansdowne Rugby Club. He left the ground to the team and to Dublin Wanderers FC and rented the pitch in 1878 for the first match between Ireland and England in history. So the legend started: in 1904 IRFU bought the land and started building the stadium in 1908.

As happens with every field, it’s neither the wood, nor the posts, nor the turf to keep Lansdowne Road’s legend alive, although the presence of the DART’s rails running under the West Upper Stand helps giving a special atmosphere to this temple of Irish rugby. The real fuel for the legend, anyway, is the tears, the beers and the sweat of players and supporters. And, in Lansdowne Road’s case, it’s the crowd chanting: the Irish supporters are always ready to sing the traditional ballad Fields of Athenry to encourage their team when it’s facing trouble, and they’re also ready to applaud a good play by the other team. Another thing which creates that legendary atmosphere is the official pre-match protocol: the President of the Republic walks on a red carpet and shakes hands with all the players. In 2003 the English stood on President Mary McAleese’s way, forcing her to walk on grass. The whole crowd got up and sang Fields of Athenry until the English cleared the way. The epic taste of Lansdowne Road is also a result of the two anthems sung before rugby matches: A Soldier’s Song (Amhrán na bhFiann), the Irish National Anthem, to represent the host country, Eire, and then Ireland’s Call, the Irish rugby team’s anthem, written to represent both players from the Republic and from Northern Ireland.

As happens with every field, it’s neither the wood, nor the posts, nor the turf to keep Lansdowne Road’s legend alive, although the presence of the DART’s rails running under the West Upper Stand helps giving a special atmosphere to this temple of Irish rugby. The real fuel for the legend, anyway, is the tears, the beers and the sweat of players and supporters. And, in Lansdowne Road’s case, it’s the crowd chanting: the Irish supporters are always ready to sing the traditional ballad Fields of Athenry to encourage their team when it’s facing trouble, and they’re also ready to applaud a good play by the other team. Another thing which creates that legendary atmosphere is the official pre-match protocol: the President of the Republic walks on a red carpet and shakes hands with all the players. In 2003 the English stood on President Mary McAleese’s way, forcing her to walk on grass. The whole crowd got up and sang Fields of Athenry until the English cleared the way. The epic taste of Lansdowne Road is also a result of the two anthems sung before rugby matches: A Soldier’s Song (Amhrán na bhFiann), the Irish National Anthem, to represent the host country, Eire, and then Ireland’s Call, the Irish rugby team’s anthem, written to represent both players from the Republic and from Northern Ireland.

A casket of tales, legends and history, as we were saying: in August 1914, the day after United Kingdom declared war, three hundred and fifty rugbymen assembled on the ground and decided to join the Royal Dublin Fusiliers as a Pals Battalion. Pals Battalions were corps invented by sir Henry Rawlinson to encourage enlisting in the Army: volounteers could enrol locally and know they were going to serve alongside their friends and work colleagues. In 1927 the East Stand was built: some delays in the works caused the roof of the stand not to be erected in time for the match against Scotland, which is remembered for its appalling weather conditions and torrential rain.

In 1929, when the field hadn’t reached yet the current capacity of 49250 people, Lansdowne Road received 40000 supporters for a match against Scotland. The crowd was too much for the terraces and stands of the stadium, so people thronged the pitch. When Irish center Jack Arigho crossed the whitewash, he wasn’t able to ground the ball between the posts, the try-area being invaded by lots of rejoicing supporters. In the same match, referee Cumberledge didn’t award winger Rowland Byers’s try because too many people were standing in the field. The stories about Lansdowne Road are also about its strong wind: Mike Watkins, legendary Welsh stand-off, once told: “At the kick-off I didn’t understand what was going on: the flags were fluttering in all directions”, while Italian prop Martin Castrogiovanni remembers: “The flags were bent to the ground, struggling to cling on earth. Some friends from Argentina weren’t even able to lay out a banner for me: wind would have tore it from their hands!”.

In 1929, when the field hadn’t reached yet the current capacity of 49250 people, Lansdowne Road received 40000 supporters for a match against Scotland. The crowd was too much for the terraces and stands of the stadium, so people thronged the pitch. When Irish center Jack Arigho crossed the whitewash, he wasn’t able to ground the ball between the posts, the try-area being invaded by lots of rejoicing supporters. In the same match, referee Cumberledge didn’t award winger Rowland Byers’s try because too many people were standing in the field. The stories about Lansdowne Road are also about its strong wind: Mike Watkins, legendary Welsh stand-off, once told: “At the kick-off I didn’t understand what was going on: the flags were fluttering in all directions”, while Italian prop Martin Castrogiovanni remembers: “The flags were bent to the ground, struggling to cling on earth. Some friends from Argentina weren’t even able to lay out a banner for me: wind would have tore it from their hands!”.

Lansdowne Road wasn’t Ireland’s only home stadium until 1954: Dublin and Belfast hosted matches alternatively. Saturday 27th February 1954: a few hours before the match scheduled at Ravenhill (Belfast’s rugby field), six Northern Irish players spoke to captain James McCarthy. “We’re honoured to be called to serve our National Team – they said – but we don’t want to stand on Irish soil and hear the band play God Save The Queen!”. Those few hours saw desperate negotiation between the Union and the players, until a compromise was found: since that Ireland-Scotland on, the greens have never played in Northern Ireland anymore (after 53 years Ireland will go back to the six counties next August, for a test-match against Italy). So Lansdowne Road became the home of Irish rugby, and IRFU moved its offices to the stadium.

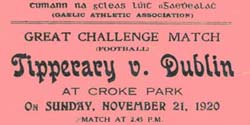

The traditions crumbling along with this stadium (perhaps the most romantic of rugby fields) are not only oval matters: the dismissal of Lansdowne Road caused the repeal of Rule 42. Rule 42 is part of Cumann Lúthchleas Gael (also known as GAA, the Gaelic Athletic Association) and denies hospitality to British sports, like football and rugby. A rule whose roots have to be sought in the Bloody Sunday of 21st November 1920, during the Irish Independence War, when the Black and Tans (a special corp of the British Army) broke into Croke Park, Dublin’s GAA stadium, during a gaelic football match between the representatives of Dublin and Tipperary. The Black and Tans raided the ground and killed a player and 14 supporters, including three boys of 10, 11 and 14. Rule 42, though, doesn’t exist anymore, and lies buried underneath Lansdowne Road’s ruins: last year GAA voted the repeal of the article, thus conceding provisional hospitality to the Irish teams of football and rugby at the Croker. Another turning point for Irish sport and all it means for the culture and society of the nation.

The traditions crumbling along with this stadium (perhaps the most romantic of rugby fields) are not only oval matters: the dismissal of Lansdowne Road caused the repeal of Rule 42. Rule 42 is part of Cumann Lúthchleas Gael (also known as GAA, the Gaelic Athletic Association) and denies hospitality to British sports, like football and rugby. A rule whose roots have to be sought in the Bloody Sunday of 21st November 1920, during the Irish Independence War, when the Black and Tans (a special corp of the British Army) broke into Croke Park, Dublin’s GAA stadium, during a gaelic football match between the representatives of Dublin and Tipperary. The Black and Tans raided the ground and killed a player and 14 supporters, including three boys of 10, 11 and 14. Rule 42, though, doesn’t exist anymore, and lies buried underneath Lansdowne Road’s ruins: last year GAA voted the repeal of the article, thus conceding provisional hospitality to the Irish teams of football and rugby at the Croker. Another turning point for Irish sport and all it means for the culture and society of the nation.

The parting glass was the afternoon of the 31st December, when the venue hosted the Celtic League match between the Irish provinces of Leinster and Ulster. The home side overcame the visitors 20-12, thanks to the tries scored by winger Denis Hickie, lock Owen Finegan and eightman Jamie Heaslip, the last ever man to score a fiver on that field. The match, dubbed by the medias as “The Last Stand”, was attended, despite the rain, by a record-crowd of 48000 and a marriage proposal even took place on the ground between the two halves of the game. The last of a thousand tales of a field that didn’t seem tired of telling stories.