11 settembre diede ad IRA la possibilità di uscire dalla “guerra”

How 9/11 gave the IRA an exit route from ‘war’

The attack on the World Trade Center turned the US into a cold house for Irish republicans. So why did Gerry Adams secretly relish his new pariah status? Ed Moloney reports from New York

Riverdale in the Bronx is a part of New York where many second- or third-generation Irish-Americans really want to live. A pleasant suburb of modest detached homes and high-rise apartments, it is about as far from the derelict and racially-torn image of the Bronx as you could get.

Riverdale in the Bronx is a part of New York where many second- or third-generation Irish-Americans really want to live. A pleasant suburb of modest detached homes and high-rise apartments, it is about as far from the derelict and racially-torn image of the Bronx as you could get.

For Irish-Americans, ending up in Riverdale is a sign that they have made it out of the ghetto. For many Irish-Americans, the path to the American dream often began in lower Manhattan in overcrowded tenement buildings and then to upper Manhattan where the apartments were slightly larger.

Moving northwards up Manhattan island was a sign of upward social mobility; moving to home-owning Riverdale indicated solid economic success.

Those making the leap often brought their politics with them, in spite of their new status in life. Inwood was where Noraid located its New York headquarters and Riverdale reflected those roots; local bars hosted pro-IRA events and some of Noraid’s most active supporters lived in the area.

Riverdale is also where I moved in August 2001, to my wife’s family home, after a lengthy career as a journalist in Belfast. But any notion that I had left political violence behind was bloodily dispelled within days when al-Qaida flew passenger planes into the twin towers of lower Manhattan.

Osama bin Laden‘s astonishing assault on America that September 11 would change everything utterly, including Ireland’s politics.

The first sign of that in Riverdale came the day after the World Trade Center crumbled into dust when most of the Irish-American homes in our street hoisted the Stars and Stripes above their front doors, transforming it into an American version of the Shankill Road on July 12, or the Falls on Easter Sunday. Those flags have flown every day since, for 10 long years. What flying the flag signaled, of course, was complete agreement with President George W Bush‘s warning-cum-declaration in the wake of the attack: “Either you are with us or you are with the terrorists.”

To say that Bush’s words caused a dilemma for Irish-American supporters of the Provisional IRA would be an understatement. The IRA was labelled as ‘terrorists’ and, while it was now engaged in the peace process, it was stubbornly refusing to give up its weapons.

Why else, the question could now be asked with added force, would the IRA want to hang on to its guns unless it wanted to keep open the terrorist option; to imitate the now-execrated Osama bin Laden? The IRA’s most important constituency outside of Ireland was suddenly no longer reliable.

Why else, the question could now be asked with added force, would the IRA want to hang on to its guns unless it wanted to keep open the terrorist option; to imitate the now-execrated Osama bin Laden? The IRA’s most important constituency outside of Ireland was suddenly no longer reliable.

As Irish-American views began to turn a half-circle, George Bush’s ambassador to the Irish peace process, Richard Haass, was about to turn the screws on the republican leadership in Ireland.

On September 11, Haass was in Dublin, about to travel north to meet Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness. His mission was to read them the riot act over disclosures that the IRA had been training America’s FARC enemy in Colombia, but when news of the 9/11 attacks came through, his goal suddenly changed.

Now his message was simple, if blunt: the only way the IRA and Sinn Fein could redeem themselves was if the IRA began decommissioning its weapons.

Paradoxically, I suspect that Haass’s warning to Adams and McGuinness was as welcome as rain in a parched desert. Publicly, the republican leadership’s position on disarming was unbending – it just wasn’t going to happen. But the reality was very different.

Reassuring the rank-and-file in the IRA and Sinn Fein that guns would never be given up was how Adams and McGuinness won their hardliners over. In private conclave with supporters, IRA leaders gave repeated assurances that, if the process failed, then war would be resumed and what better way to underline that promise than by holding onto the guns. By 2001, however, it was clear that no unionist leader – least of all David Trimble – could go into government with Sinn Fein unless the implied threat in all those arms caches was removed.

The peace process was facing ignominious failure unless the logjam was broken and no-one knew that better than Adams and McGuinness.

I believed then – and even more so now – that the two men had concluded long before that the guns would have to go. The question was how to do so without causing another damaging split in the IRA.

Ironically, Osama bin Laden offered a way out and helped put the peace process back on the rails – although I doubt he would ever have wanted to claim credit.

On October 18, just six weeks after 9/11, the IRA began destroying its weaponry with barely a peep of protest from its rank-and-file. Fear of isolation had done the trick.

Bin Laden is not the only Arab leader to reshape recent Irish history.

Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, the now deposed Libyan leader, is often reviled for supporting the IRA. But doing so helped make the peace process possible.

Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, the now deposed Libyan leader, is often reviled for supporting the IRA. But doing so helped make the peace process possible.

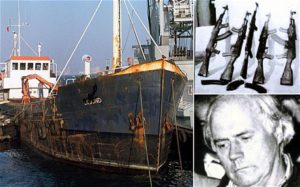

The capture of the gun-running ship the Eksund in 1987 cut off the IRA’s last possible chance of military success and strengthened the politicos in the IRA.

Meanwhile, prior shipments of weapons from the Libyan leader, especially Semtex explosives, gave the IRA leadership valuable bargaining chips to play in the negotiations, making the peace process even more alluring.

History can be really weird, can’t it?